New SMS scam drains bank accounts in 30 seconds: how to recognize it

We analyze the technical and psychological mechanism behind the new wave of banking smishing. Discover why fraudulent messages appear in authentic chat threads and how execution speed renders old defense methods ineffective.

In our daily work managing digital infrastructures and communication flows, we observe a radical shift in the nature of cyber threats. While fraud attempts were once grammatically poor and technically crude, today we face surgical operations designed to exploit not software vulnerabilities, but communication protocols and user psychology. The so-called "30-second scam" is not a sensationalist headline, but an accurate description of an operational time window during which our bank accounts can be irreversibly compromised through a simple SMS.

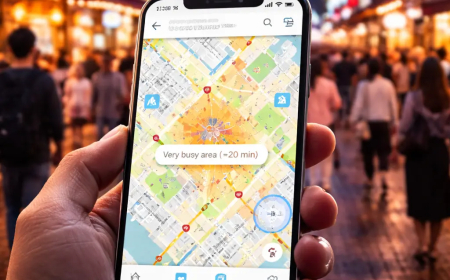

What makes this threat particularly insidious is its ability to blend perfectly into legitimate conversations. We frequently receive reports from users bewildered by the fact that the fraudulent message appeared in the same history as genuine messages sent by their bank. This phenomenon occurs because mobile network protocols allow for the manipulation of the "Sender ID," the text identifier of the sender. When criminals send a message setting the sender name to the exact name of the banking institution, the victim's smartphone, following a name-grouping logic, queues the fake message alongside authentic ones containing access codes or notifications of past transfers. At GoBooksy, we constantly see how this single logical flaw in how devices handle SMS is the keystone that breaks down the user's initial distrust.

The attack mechanics are designed to generate a sense of urgency that short-circuits rational thought. The text almost always refers to unauthorized access, a preventive card block, or a suspicious outgoing transaction. The instinctive reaction is to protect one's savings by clicking the link provided to "verify" or "block" the operation. This is where the criminal infrastructure reveals its sophistication. The link does not lead to a static site, but to a mirroring platform that faithfully reproduces the bank's interface, often updated in real-time. As the user types their credentials on the fake site, a bot or human operator simultaneously enters them on the real bank site.

The critical moment, those fateful thirty seconds, triggers when the real banking system sends the OTP (One Time Password) to authorize access or a transaction. The user, believing they are using that code to cancel a fraudulent transfer on the fake page, enters it into the form. Immediately, the criminal system intercepts that code and uses it on the real banking portal to finalize an instant transfer to foreign accounts or "money mules." Speed is essential because OTP codes have a very short validity period. We have analyzed cases where the entire process, from clicking the link to emptying the available balance, took place in less than a minute, leaving the victim with only the notification of the completed transaction.

Another often underestimated aspect is the quality of the "social engineering" used. In some more complex scenarios we have monitored, the SMS is merely the prelude to a voice call. A fake operator, who already knows the victim's name and surname thanks to previously leaked databases, calls to "assist" the user in the blocking procedure, guiding them step-by-step in providing security codes. The human voice, calm and professional, is a powerful tool to lower defenses, much more so than a web interface. This hybrid approach makes it extremely difficult to distinguish real from fake, especially in moments of emotional stress induced by the fear of losing money.

Defending against these threats requires a paradigm shift in how we interact with service communications. At GoBooksy, we adopt and recommend a "Zero Trust" approach towards the SMS channel for critical communications. The golden rule we apply is that banks and financial institutions never include direct links for account access within text messages. If there is a real problem, it will be visible by accessing the official app or website by manually typing the address, never by following a shortcut sent via message. Furthermore, it is crucial to carefully read the content of SMS messages containing OTP codes: often, in haste, one ignores that the message reads "authorize transfer" while we are convinced we are authorizing a "cancellation."

Technology offers us powerful tools, but ultimate security lies in our ability to slow down decision-making processes in the face of urgency. Understanding that a message sender can be spoofed and that the interface we see on the screen can be a mask is the first step to immunizing oneself against these frauds. True protection is found not just in antivirus software or banking firewalls, but in the awareness that, in the digital world, urgency is almost always the first sign of deception.