Did you know the QWERTY keyboard was designed to slow you down?

We analyze why we still use a layout devised in 1873 for mechanical machines. Discover how "path dependence" has stalled the evolution of digital typing and why QWERTY, designed to fix mechanical jams, dominates our touch screens today despite poor ergonomics.

It is fascinating to note how, within the beating heart of our cloud infrastructures and among the lines of code we develop every day at GoBooksy, the primary input tool remains a legacy of the 19th century. Every time we place our hands on the keyboard to type a command line or an editorial article, we are interacting with a device that was not optimized for the speed of our processors, but for the mechanical limits of an 1873 typewriter. Urban legend has it that the QWERTY layout was deliberately invented to slow typists down, but the operational reality is more nuanced and, if anything, technically more interesting for those of us dealing with workflows.

Christopher Sholes, the inventor, faced a purely physical problem: if two adjacent letters on the keyboard were pressed in rapid succession, the typewriter's hammers would clash and jam, halting work. The solution was not to sabotage the operator's speed, but to separate the most common letter pairs in the English language, forcing the fingers to travel greater distances. This local "slowing down" prevented mechanical locking, paradoxically allowing for a higher sustainable overall speed. Today we no longer have hammers that get stuck, yet we continue to move our fingers according to that obsolete logic, tacitly accepting an ergonomic inefficiency that we observe daily in our offices as well.

The persistence of this standard is one of the most glaring examples of what we in economics and technology define as "path dependence." Although alternative layouts like Dvorak or Colemak exist, scientifically studied to reduce finger movement and increase comfort by lowering tendon stress, the barrier to entry for change has become insurmountable. At GoBooksy, we often notice how muscle habit prevails over theoretical efficiency. Learning to type is a cognitive investment the average user makes once in a lifetime; asking to reprogram muscle memory to gain a marginal increase in speed is a proposition the market has systematically rejected for decades. The cost of transition outweighs the perceived benefit.

This technological inertia has tangible consequences on our health and productivity. QWERTY overloads the left hand and forces fingers into acrobatic jumps to the top and bottom rows, leaving the "home row"—the central resting row—surprisingly underutilized for the most frequent vowels and consonants. Analyzing workstation usage data, we see how this contributes to wrist fatigue and carpal tunnel syndrome, real problems we manage through physical workstation ergonomics, but which are rooted in the interface software itself.

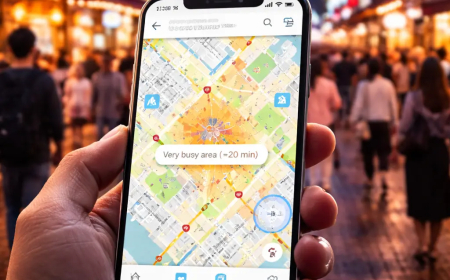

The absurdity of the design reaches its peak with the advent of mobile. We have transposed a layout designed for ten fingers onto screens of a few inches used predominantly with two thumbs. Typing errors on smartphones are endemic precisely because QWERTY was never intended for touch screens or predictive typing. Autocorrect algorithms work ceaselessly to compensate for the intrinsic inaccuracy of this system, creating a layer of software complexity necessary only to mitigate inadequate hardware design. It is a paradox we live daily: we use artificial intelligence to correct errors induced by a Victorian-era key arrangement.

Reflecting on the QWERTY keyboard serves to help us understand how technological choices are often the result of historical compromises crystallized in time rather than real functional optimization. We will continue to use it because it is the universal language with which machines and humans have agreed to communicate, sacrificing ergonomics on the altar of global standardization. The lesson we draw is that the best technology is not always the one that wins; often, the winner is the one that arrives first and roots itself deeply enough to make change too costly.