Smartphone Battery Dying Faster? The Truth Manufacturers Avoid

We analyze why smartphone battery life plummets after the first year. We uncover the chemical dynamics, the real impact of fast charging, and how design choices influence longevity, debunking myths and confirming concrete physical limits.

In our daily work at GoBooksy, where we manage operational workflows and complex digital infrastructures, we constantly confront one of modern technology's most frustrating physical limits: energy autonomy. Not a day goes by without us observing how flagship devices, seemingly perfect on paper, begin to show signs of energy fatigue far sooner than promised by spec sheets. The commercial narrative has conditioned us to believe that if the battery doesn't last, the fault lies exclusively with our intensive usage or some poorly programmed application, but the reality we encounter in our labs and in the field is quite different and deserves an honest explanation.

The first fact we must reckon with is the intrinsically perishable nature of lithium-ion technology. We are not talking about a manufacturing defect, but an unavoidable chemical characteristic often omitted in mainstream communication. Every time we use a smartphone for our digital publishing activities or cloud process management, we are consuming vital cycles of the energy cell. Inside the battery, a physical movement of ions occurs between the cathode and anode which, over time, alters the chemical structure of the materials, reducing their capacity to hold energy. It is an aging process that begins the very moment the device is assembled, not when we turn it on for the first time.

A critical aspect we have detected while analyzing usage data concerns thermal management and the highly praised ultra-fast charging. The industry pushes for increasingly shorter charging times, promising 100% in just a few minutes, but rarely explains the price paid for this convenience. Speed generates heat, and heat is the number one enemy of batteries. When we force a large amount of energy into a confined space in a very short time, internal resistance increases and the temperature rises, accelerating electrolyte crystallization. In our tests, we have noticed that devices systematically recharged with high-wattage chargers tend to lose maximum capacity much faster than those charged slowly and at controlled temperatures.

There is also a notable discrepancy between increasingly powerful hardware and increasingly slim design. Physics imposes precise rules: to have more autonomy, you need more volume. However, the market trend demands phones that are thin, light, and aesthetically appealing. Manufacturers are forced to sacrifice space dedicated to the battery to make room for massive camera modules and complex cooling systems. The result is that the smartphone's "engine," the processor, becomes increasingly demanding in terms of resources to handle high-refresh-rate screens and 5G connectivity, while the "fuel tank" remains dimensionally unchanged or grows only marginally. Declared autonomy is often based on laboratory tests performed under ideal conditions, with reduced brightness and minimal background processes, a scenario that never reflects the real-world usage that we at GoBooksy and our users engage in daily.

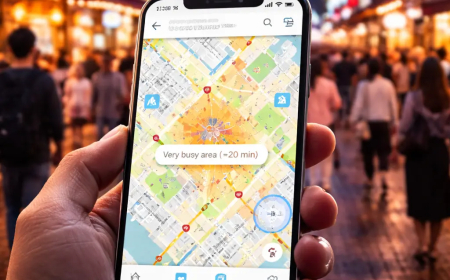

Software also plays a fundamental role, often underestimated. We refer not only to energy-consuming apps but to the continuous dialogue between the device and remote servers. Constant data synchronization, automatic backups, and the ceaseless search for the best available network create a "phantom" consumption that drains the battery even when the phone is in your pocket. We have verified how unstable network coverage is one of the main causes of anomalous consumption: the phone's modem works at maximum power to maintain the signal, consuming more energy than the screen itself.

To mitigate this inevitable degradation, the operational approach must change. Instead of looking for miraculous software solutions, it is necessary to adopt different physical habits. Keeping the charge between 20% and 80% is not an urban legend, but the most effective way to reduce chemical stress inside the cell, avoiding the extreme tension states that occur when the battery is completely drained or fully full. Leaving the phone charging all night, although modern power management systems are intelligent, still keeps the battery at high voltage for hours, reducing its longevity in the long run.

The truth emerging from our operational experience is that the battery is a consumable item, destined to run out. User frustration stems from an unrealistic expectation of performative eternity that does not belong to current chemistry. Understanding that heat, deep charging cycles, and energy density are physical limits and not software bugs allows us to use technology with greater awareness, accepting that battery life is the necessary compromise to have a computer in our pocket capable of connecting us with the entire world in real time.