The Invisible Pixel: How Newsletters Know Exactly When (and Where) You Open Them

A technical journey into email infrastructure: discovering how a transparent single-pixel image transforms reading into data, revealing opens, devices, and locations, and why new privacy policies are making these signals increasingly uncertain.

"The Invisible Pixel: How Newsletters Know Exactly When (and Where) You Open Them"

Opening an email feels like the most passive and private digital act imaginable. We sit in front of the screen, click on the subject line that caught our attention, and read the content in solitude. Yet, the precise moment the text appears on the display, a silent signal leaves our device to travel across the network and knock on a remote server's door. We haven't clicked anything, we haven't filled out forms, but the sender knows we are there. At GoBooksy, we observe this data exchange daily, managing communication flows that rely on this technology, which is as simple as it is controversial: the tracking pixel.

Everything revolves around a graphic element that the human eye cannot perceive. Embedded within the HTML code that makes up the newsletter is a 1x1 pixel image, often transparent or matching the background color. When the email client downloads images to display the full email, it is forced to download that tiny invisible dot as well. To do so, it must send a request to the server where the image is hosted. It is within this request that the informational exchange occurs. The server does not merely deliver the image but logs the call, noting the originating IP address, the exact time of the request, and the User-Agent string, which reveals whether we are using an iPhone, a Windows PC, or an Android tablet.

In our daily work on infrastructures and distribution platforms, we often notice how non-technical users overestimate the "magical" precision of these tools or, conversely, remain completely unaware that they are being watched. The technical reality is that the pixel is not spyware installed on the computer but exploits the standard functioning of the HTTP protocol. Every time a web page or an email loads an external resource, it leaves a trace in the server logs. The sender uses this trace to calculate the open rate, a metric that for years has been the undisputed beacon of digital communication strategies.

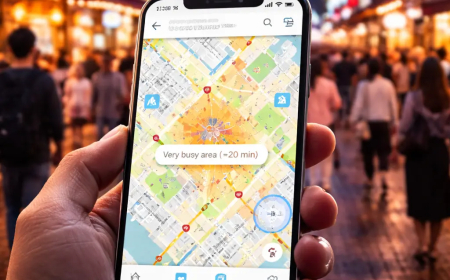

However, the landscape is shifting radically, and the data we read in reports today no longer tells the same story as five years ago. Geographic precision, for instance, has become a blurred concept. While in the past an IP address could indicate a user's neighborhood or city with good approximation, today the spread of VPNs and corporate architectures makes this datum increasingly generic. Furthermore, major email providers have started placing themselves between the sender and the recipient to protect the latter's privacy, forever altering how tracking works.

The most striking case we have faced while adapting our project strategies concerns the introduction of Mail Privacy Protection by Apple. This system pre-loads email images, including tracking pixels, onto intermediate proxy servers before the user even opens the message. From the sender's perspective, the email appears "opened" almost instantly, even if the recipient never read it and perhaps sent it straight to the trash. This generates an inflation of open data that renders old metrics unreliable. We constantly see databases showing seemingly sky-high engagement rates that do not correspond to real human interest, but merely to the automated activity of Apple's servers "cleaning" the emails.

This dynamic has forced the entire sector, GoBooksy included, to reconsider what it truly means to measure the success of a communication. The invisible pixel continues to function, but its signal has become noisy. We can no longer blindly trust the "who" and the "where." An open recorded in Milan might actually be a user in Rome using a provider with exit nodes in the Lombard capital. An open recorded at three in the morning could be an automated process by the email provider scanning the message for malware, simulating human behavior.

The operational consequences of these inaccuracies are tangible. Automations based on opens, such as sending a second email to someone who hasn't read the first, risk failing or becoming intrusive toward people who had actually already interacted with the message through provider filters. We are shifting attention from passive opening to active action. A click on a link, a direct reply, or navigation to the website remain the only unequivocal indicators of real interest. The pixel survives as a statistical tool to observe large numbers, but it has lost its ability to act as a precision scope on the individual.

Tracking pixel technology teaches us a fundamental lesson about today's digital ecosystem: the map is not the territory. What we see in control panels is always a representation mediated by filters, proxies, caches, and security protocols. Understanding that behind that small transparent dot lies a complex negotiation between server and client helps us read our own inbox with greater awareness and interpret marketing data not as absolute truths, but as signals in an environment increasingly attentive to confidentiality.