The Weight of Knowledge: Why the Internet Weighs as Much as a Strawberry but Consumes Like a Nation

The Internet is not as ethereal as it seems. Although the mass of electrons comprising global data is estimated at just 50 grams, the infrastructural reality tells a different story of cables, servers, and energy. We analyze the physicality of digital existence and its operational consequences.

There is a fascinating paradox that often circulates among experts and theoretical physicists, a concept that transforms the entire global network into a small, tangible object. According to calculations based on the mass of electrons required to encode and transmit information, the entire Internet would weigh approximately 50 grams. It is a powerful image: all human knowledge, videos, financial transactions, and communications we handle every day, enclosed within the specific weight of a large strawberry. However, when we at GoBooksy step into a server room or design a cloud architecture, the physical sensation we perceive is diametrically opposed to that lightness.

The idea that the digital world is ethereal, an impalpable "cloud" floating above our heads, is perhaps the greatest misconception of our age. This belief often leads companies and users to treat data as infinite resources without impact, forgetting that every byte has real physical consistency. When we upload content online, we are moving subatomic particles that require immense energy effort to be maintained in an ordered state. The theoretical weight of electrons is insignificant if isolated, but it becomes an operational boulder when we consider the container necessary to keep those electrons from dispersing.

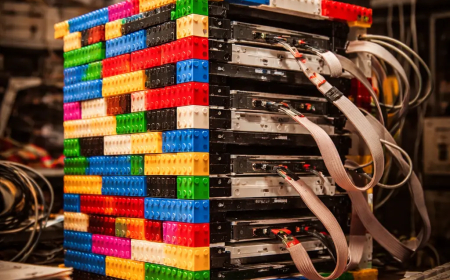

In our daily work with network infrastructures, we observe that the lightness of software constantly clashes with the heaviness of hardware. To keep those famous 50 grams of active data alive, humanity has built one of the largest and most complex machines in history. The data centers we use to host websites and applications are nothing more than huge physical warehouses where electrical energy is converted into heat and calculations. The "weight" of the Internet, therefore, is not to be found in the atomic mass of data, but in the tons of copper, fiber optics, silicon, steel, and water for cooling that make the existence of that data possible.

This discrepancy between the theoretical weight of information and the real weight of infrastructure has immediate practical consequences. We often find ourselves explaining that optimizing a website or a database is not just a matter of loading speed, but of applied physics. Unoptimized code or uselessly heavy images force processors to work harder, moving more electrons and generating more heat. This translates into higher energy consumption and, ultimately, higher operational costs and a more marked environmental impact. The digital "strawberry," if not managed correctly, rots quickly, becoming a raw cost.

We have noticed that the perception of the web's immateriality drives many to practice a sort of compulsive digital hoarding. Since we do not see the physical space occupied by old emails, redundant backups, or unused graphic assets, we tend to keep everything. But at GoBooksy, we know well that disk space, even if virtualized in the cloud, corresponds to magnetic sectors on a hard drive or memory cells in a solid-state drive that must be powered 24 hours a day. Deleting useless data is a physical act: it means freeing up resources, reducing energy demand, and lightening the load on cooling systems that fight against thermodynamics to prevent servers from melting.

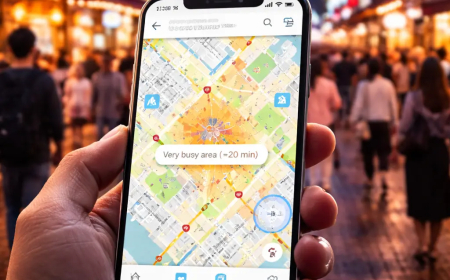

The current technical challenge is no longer just connecting people, but doing so while making the weight of this connection sustainable. The transition to serverless architectures or the use of geographically distributed CDNs (Content Delivery Networks) are direct responses to the need to bring data closer to the user, reducing the distance electrons must travel. Less distance means less resistance, less dissipated heat, and more efficient management of those crucial 50 grams. Every time we improve the efficiency of a data flow, we are literally reducing the physical friction that the Internet exerts on the real world.

Recognizing the physical nature of the network changes the way we design and consume technology. We are not handling magic, but matter and energy. The awareness that behind every click lies a movement of particles and a consumption of resources imposes a greater responsibility on us to create clean and essential digital ecosystems. The Internet may weigh as much as a strawberry in electron theory, but its footprint on the planet is as heavy as the steel and concrete that support it. Understanding this duality is the first step to building a digital future that is not only fast but also concretely sustainable.