Innovation starts with bricks: why Google's first server was made of LEGO

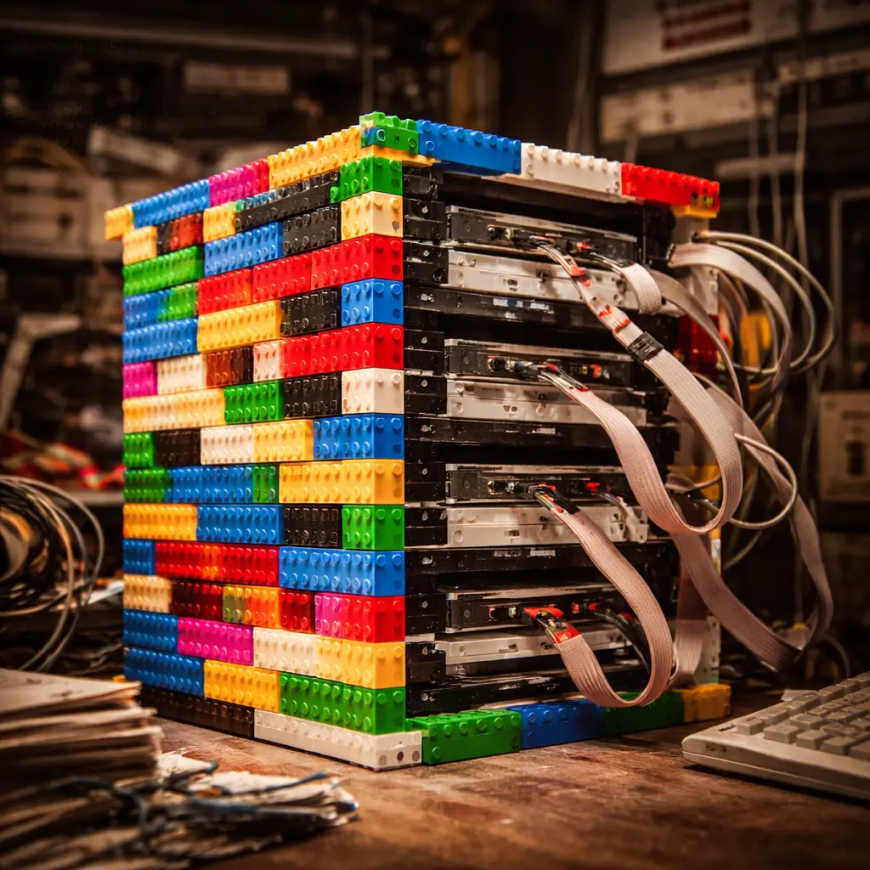

In 1996, a 40 GB server housed in a LEGO case changed the concept of data centers forever. We analyze how that cost-effective and modular choice laid the foundations for modern cloud computing and the hardware philosophy we use today.

A colorful case for a digital revolution

When we think of modern data centers, we imagine sterile corridors, blue LED lights, and standardized metal rack cabinets humming in temperature-controlled environments. Yet, the genesis of everything we take for granted today in online search and data storage lies in a much humbler structure, assembled with patience and colorful bricks. In our daily work at GoBooksy, where we manage complex data flows and critical infrastructures, we often look to the past to understand the evolution of efficiency, and Google's first server represents a perfect case study of pragmatic engineering.

In 1996, Larry Page and Sergey Brin found themselves at Stanford with a very concrete problem and an extremely limited budget. Their algorithm, BackRub (which would later become Google), required storage space that was monstrous for the time: 40 gigabytes. To achieve that capacity, they had to combine ten hard drives of 4 gigabytes each. The problem was not just electronic, but physical. There were no low-cost computer cases capable of housing ten disk units simultaneously in a secure and accessible way. The solution did not come from an enterprise hardware supplier, but from a box of LEGO Duplo.

The engineering logic behind the toy

The choice of bricks was not an aesthetic whim or an eccentricity of odd students, but a brilliant technical response to real constraints. Building the case with LEGO allowed Google's founders to create a perfectly modular and expandable architecture at almost zero cost. This flexibility is a concept we constantly apply in our software architectures today: the ability to scale and modify the supporting structure without having to tear down and rebuild the entire system.

The bricks allowed the hard drives to be spaced optimally for heat dissipation, a problem that still plagues those who design high-density server farms today. Plastic, despite being an insulator, in the open configuration created by Page and Brin, favored an airflow that the closed, cheap metal cases of the time could not guarantee. Looking at that primordial structure, we recognize the founding principle of "rapid prototyping": build, test, fail, modify, and try again with immediately available materials. At GoBooksy, we often find ourselves assembling temporary solutions to test traffic flows or new cloud configurations, and the spirit of adaptation of that first server remains a fundamental lesson on how function must always prevail over form.

The birth of Commodity Hardware

That strange colorful assembly hid a philosophical revolution that destroyed the traditional mainframe market. Until then, large companies relied on expensive monolithic servers produced by giants like IBM or Sun Microsystems. Google's approach, symbolized by the LEGOs, was the opposite: use consumer hardware ("commodity hardware"), cheap and easily available, and entrust the software with the task of managing failures.

If a disk broke, a specialized technician wasn't needed to repair a complex proprietary system; it was enough to detach the piece and replace it, just like a brick. This is the foundation upon which the entire modern cloud ecosystem we use for our clients rests. Redundancy is no longer guaranteed by the perfection of the single hardware component, but by the resilience of the distributed system. That 40 GB server demonstrated that a battery of cheap and imperfect machines, if orchestrated correctly, is superior to a single perfect supercomputer.

From the dorm room to the global cloud

Today, the legacy of that server is reflected in big data management and virtualization. The need to host huge amounts of information with limited resources has pushed the industry towards containerization and resource orchestration, concepts that are the daily bread for those who, like us, develop digital infrastructures. We no longer build cases with bricks, but we build software infrastructures that maintain that same modularity: microservices that can be added, removed, or moved without the entire ecosystem collapsing.

It is fascinating to note how, despite technology having made giant strides in terms of computational power, the challenges remain the same: heat management, space optimization, cost reduction, and scalability. The first Google server reminds us that innovation does not necessarily require unlimited budgets or unreachable futuristic technologies. Often, the most effective solution lies in the ability to look at common objects and complex problems from a lateral perspective, transforming an economic limit into a structural advantage. True computing power lies not in the silicon, but in the architecture that governs it.